I have selected one book from my reading in each of the years of the decade ending this year. The list includes contemporary novels, plays, non-fiction, and classics. I had to make some difficult choices because I often felt more than one book that I read in a given year qualified. I also limited the list to one book for any given author*. If I had not done this both Cormac McCarthy and Thomas Mann would have been represented twice. All of these books are among those I would reread (and in some cases have already done so), but I am looking forward to the new decade with anticipation of meeting new great books by authors both familiar and not.

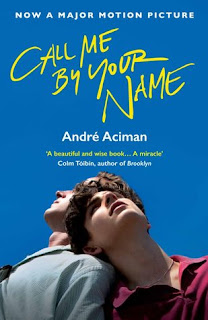

2010 Call Me By Your Name by Andre Aciman

2011 The Double Helix by James D. Watson

2012 Walden by Henry David Thoreau

2013 The Coast of Utopia, a trilogy of plays by Tom Stoppard

2014 The Roots of Heaven by Romain Gary

2015 Death in Venice by Thomas Mann

2016 The Death of Virgil by Hermann Broch

2017 Suttree by Cormac McCarthy

2018 The Divine Comedy by Dante

2019 The Periodic Table by Primo Levi

* Some of the books that almost made the list included Richard Flanagan's The Narrow Road to the Deep North, Mc Carthy's Border Trilogy and The Road, Elias Canetti's Auto Da Fe, Mann's Doctor Faustus, and Rabih Alameddine's An Unnecessary Woman.