Glenn Gould

“If music be the food of love, play on,

Give me excess of it; that surfeiting,

The appetite may sicken, and so die.”

― William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night

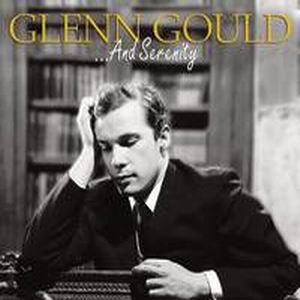

Each day I listen to a little music from one of my collection of Cd's (sometimes more). The delight in revisiting old musical friends or hearing a new composition and finding sounds to accompany my moods is only part of the experience. On this day, near the end of the year, what better way to spend part of the time as the earth spins inevitably toward the new year than with the unique pianistic voice of Glenn Gould. I was moved again by his interpretation of Bach, of course; but also his Brahms, Mendelssohn, Scriabin and others from a collection entitled simply: "Glenn Gould ...And Serenity". The sounds were serene and even in the more familiar works were new again in his hands. Perhaps he said it best:

“I believe that the justification of art is the internal combustion it ignites in the hearts of men and not its shallow, externalized, public manifestations. The purpose of art is not the release of a momentary ejection of adrenaline but is, rather, the gradual, lifelong construction of a state of wonder and serenity.” ― Glenn Gould